Over a Century of Food and Change in Chinatown

Manhattan’s Chinatown offers dishes and menus from diverse regions for residents and visitors alike. Though today the neighborhood has a thriving cultural and culinary community, such a variety in food and foodways was absent in the mid-1800s when Chinatown as we know it began.

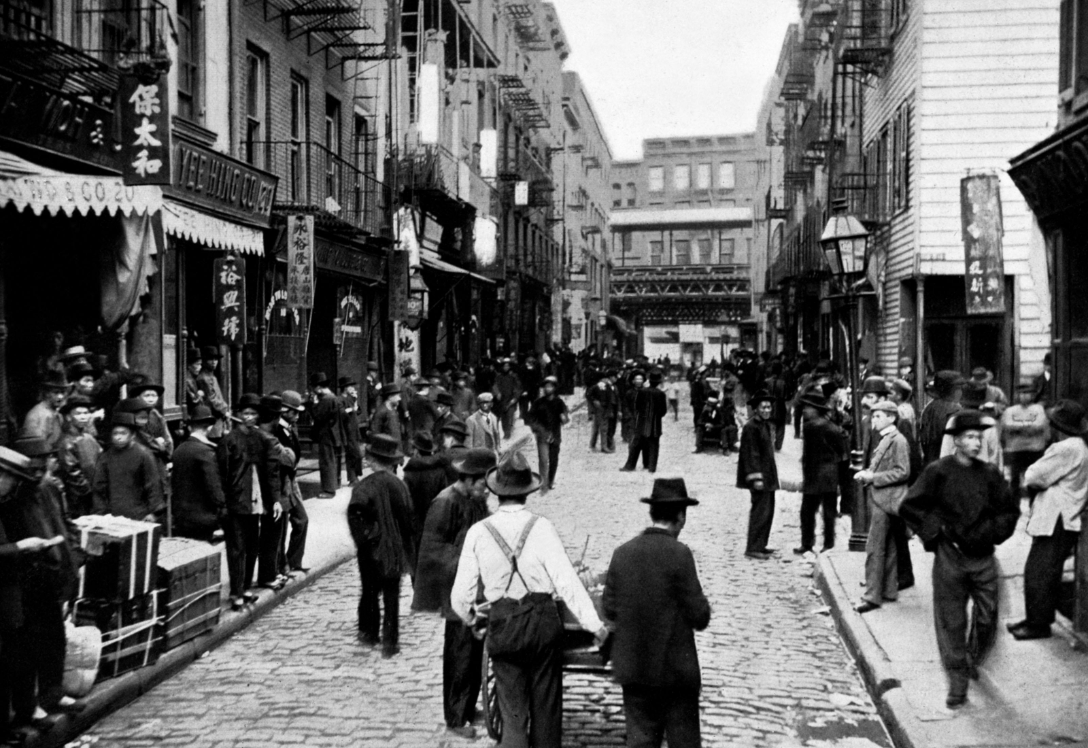

It wasn’t until the 1870s that Chinese immigrants began to arrive in New York in sizeable numbers, and what’s now known as Chinatown was established. The term itself — “China Town” — was first used by the New York Times in 1880 to describe an area defined by three streets that still form its heart: Mott, Pell, and Doyers. Some early Chinese New Yorkers were sailors and traders who arrived directly in New York’s port and decided to stay, but many of the neighborhood’s early residents arrived not from China directly, but from the western United States, particularly in the wake of anti-Chinese riots in San Francisco in 1877. Some had mined and panned for gold during the California Gold Rush; others had been part of construction crews building the first transcontinental railroad.

At the time, there were virtually no restrictions on Chinese immigration to the United States, and by the early 1880s Chinatown teemed with department stores, laundries, curio shops selling paper fans and jade rings, and small restaurants. Soon the thrum of Chinatown spilled out into adjacent streets like Bayard, Elizabeth, and Mulberry. But this expansion came to an abrupt halt after 1882, with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act by Congress, which slowed immigration to a trickle. In the year of the act, 40,000 people of Chinese origin arrived in the United States; in 1887, the country allowed entry to only 10.

Chinatown’s earliest eateries were small tea houses and rice shops that catered mostly to immigrants — by 1888, there was a handful of these restaurants in a radius of just a few blocks. But larger establishments soon began to appear, aimed at Chinese and non-Chinese alike. In 1897 Port Arthur Restaurant debuted, the largest Chinese restaurant in the city so far. It occupied the second and third floors of 7-9 Mott Street (a department store called Soy Kee & Co. rented the ground floor) and was ornately furnished with carved teakwood chairs and tables imported from China. The second floor was open to the general public, while the third was a labyrinth of dining rooms dedicated to private banquets, mainly weddings, birthdays, and funerals. (Port Arthur remained open at that location for nearly 85 years.)

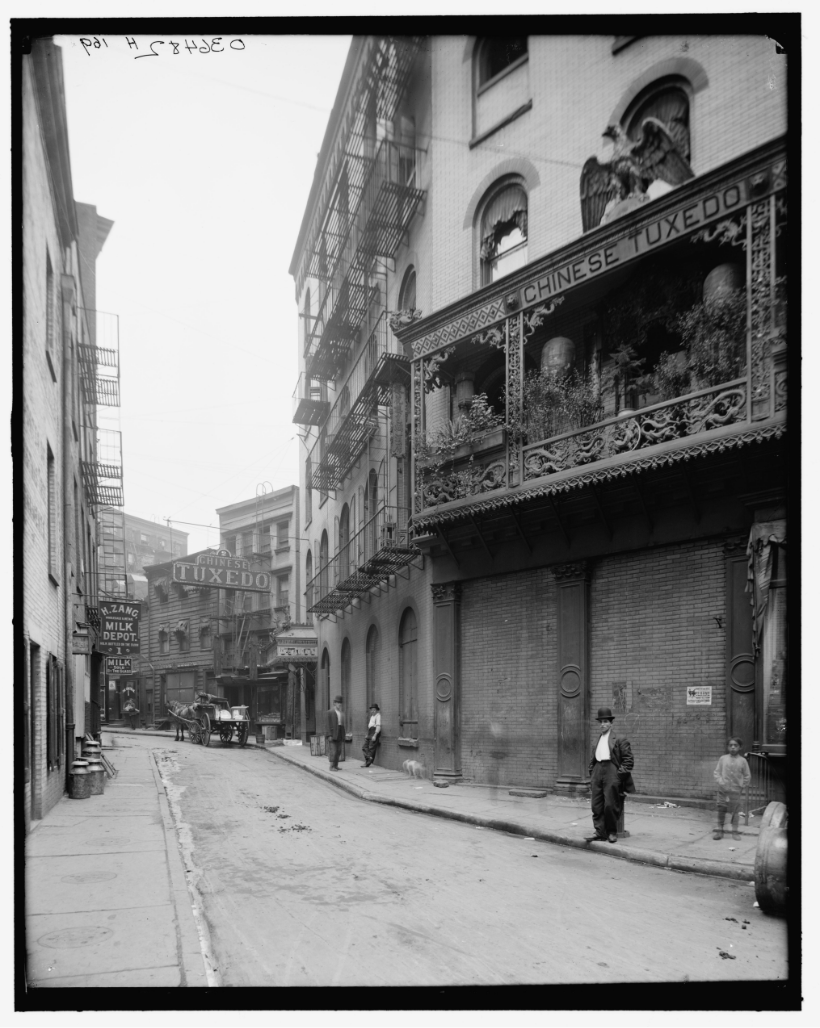

But food was not the only thing the Chinatown of the 1890s became known for. Perhaps because it had earlier been part of the hardscrabble neighborhood known as Five Points, and also perhaps because early Chinese residents were subject to prejudice from the press and general population, the community developed a reputation for crime, prostitution, and drug use.

A popular turn-of-the-century newspaper called the Police Gazette was filled with lurid accounts of Chinatown battles featuring hatchet-wielding warriors fighting on behalf of the tongs, secret societies engaged in criminal activities, of which there were two: the Hip Sings and the On Leongs. The sharp bend in Doyers Street, a blind corner, was the site of several murders, becoming known as the Bloody Angle. It reportedly provided a secret getaway route to Mott Street through underground passageways.

The general public also exhibited a powerful fascination for Chinatown’s opium dens (even though their patrons were often non-Chinese), and soon wealthier uptowners began to engage in a practice called “slumming.” This popular pastime was essentially class tourism: sightseeing in impoverished neighborhoods to see how the poor lived. The slummers came to Chinatown with the intent to stare at murder sites and tour opium dens (which were sometimes faked), and often stayed to eat and shop.

Meanwhile, a particular Chinese American cuisine was developing in America, distinct from the regional fare of places like Guangzhou and Chaoshan, where many immigrants came from. It began with mining camp and transcontinental railroad cooks, who resourcefully used local vegetables, dried seafood, and canned ingredients from San Francisco to construct some semblance of the food of home — substituting shredded cabbage for bean sprouts, for example. The evolution continued as savvy cooks reformulated dishes for non-Chinese palates, since, as the 20th century dawned, Chinese restaurants were increasingly patronized by non-Chinese diners.

Chop suey — a flexible, thrown-together stir-fry — may be the earliest Chinese American dish, with chow mein featuring crunchy noodles its close follower. But the perfect example of this new, cobbled-together cuisine might be egg foo young: a wok-fried omelet full of Chinese vegetables, and sometimes meat or seafood, smothered in European-style brown gravy, and plunked on top of fluffy and fragrant polished rice. Though Chinese American cuisine evolved in the 1970s, as diners’ and restaurants’ attention shifted to regional Chinese cooking imported to local kitchens, the old-fashioned menu still lives on in New York City’s neighborhood carryout restaurants, and in a handful of the older places still found on those original blocks of Manhattan’s Chinatown, like Hop Kee and Wo Hop.

The borders of Manhattan’s Chinatown remained firmly fixed for nearly 80 years after 1882: an area of approximately eight blocks bounded by Canal Street on the north, Bowery on the east, Baxter Street on the west, and Worth Street on the south. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the Magnuson Act of 1943; it allowed Chinese immigrants to enter the country legally, but their right to own property and establish businesses was still restricted. It wouldn’t be until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that Chinese citizens and immigrants were granted full rights, and Chinatown began to expand again.

Between 1965 and 2000, Chinatown swelled to 10 times its earlier size, growing to occupy much of the Lower East Side. While the original neighborhood had traditionally been a Cantonese enclave, the makeup of the residents began to shift in the 1960s, with a wave of immigrants from Hong Kong coming in the late ’60s and early ’70s and another arriving around the time when the former British colony was returned to China in 1997. The American loss of the Vietnam War brought many ethnically Chinese immigrants people who’d once lived in the Mekong Delta to the neighborhood, and Vietnamese restaurants soon became a fixture of Chinatown, especially on Baxter, Centre, Hester, and Grand streets. Others came from Malaysia and the Philippines.

But by far the largest group of newcomers came in the 1980s, hailing from Fujian, a province on the southeast coast of China. They spoke a dialect very different from Cantonese, and had trouble communicating with earlier Chinatown residents. East Broadway — originally a largely Jewish street — became almost wholly Fujianese, as many cafes, vegetable stands, fish markets, temples, employment agencies, and bus ticket sales offices sprung up. Many of the immigrants arrived illegally and at great personal risk, paying smugglers known as “snakeheads” as much as $40,000 apiece for the privilege.

The influx of Fujianese immigrants transformed many parts of the Lower East Side, particularly on Eldridge and Forsyth streets (in addition to East Broadway) — sometimes taking over former Cantonese restaurants, but more often establishing new places all their own. Migrants from Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian province, brought Fuzhounese cuisine, known for its light sauces and fresh preparations. These restaurants often specialized in dumplings and hand-pulled noodles sold at extremely low prices, as the new immigrants worked for very low wages, and couldn’t afford meals that cost more than a few dollars. These cheap eateries also attracted students and other New Yorkers intent on dining inexpensively.

But this new Chinatown population also had a cuisine very different from the Cantonese food that had long been the neighborhood’s mainstay. Along Division Street and East Broadway emerged a series of small cafes that displayed their wares in the windows, 30 or more selections at a time (today priced at three for $5) which came with a big plate of rice and a perfunctory cup of soup. Ensconced in metal pots were small fried fish, tiny dried scallops stewed with green vegetables, fried eggs, pork-stuffed fish balls, and lychee pork.

Manhattan’s Chinatown became something of a national capital for the country’s new Fujianese population, many of whom arrived here only to depart on discount buses for other cities — Boston; Philadelphia; Alexandria, VA; Charlotte, NC, and beyond — to work in Chinese restaurants and other businesses. The transplanted Fujianese would return periodically to New York’s Chinatown to stock up on familiar groceries and other supplies not available in their new homes, riding the same network of discount buses, which soon also became a source of cheap transit for budget-minded students and European backpackers.

In the new century, suddenly there was an influx of immigration — increasingly through legal channels — from various Chinese provinces, a change reflected in the number of regional cuisines represented in the neighborhood’s restaurants. In 2000, there were suddenly nearly a dozen restaurants specializing in the food of Shanghai, with its braised pork shoulders and orange-scented lion’s head meatballs. A restaurant called Joe’s Shanghai, opened in 1995, launched a craze for Shanghai soup dumplings, which became a citywide obsession.

Fiery Sichuan cuisine continued to grow in popularity; a fad had started on the Upper West Side in the 1970s and zoomed to new heights nearly 40 years later. Soon there were restaurants with menus hailing from Henan, Xi’an, and Beijing itself — though many northern Chinese immigrants from places like Dongbei, Qingdao, and Tianjin chose to settle in the Chinatown in Flushing, Queens, a newer enclave which had once been (and still partly remains) a Taiwanese neighborhood.

Additional Chinatowns sprung up in Elmhurst, Queens (favored by Chinese from Southeast Asia); Sunset Park, Brooklyn (originally occupied by wealthier Cantonese, but now increasingly Fujianese); and Bensonhurst, Brooklyn — which almost didn’t qualify as a Chinatown due to the dispersal of Chinese businesses among Russian, Italian, Turkish, Central Asian, and Central American ones. Meanwhile, Manhattan’s Chinatown has gradually suffered encroachment from the young and affluent, and storefronts that were once Chinese have become cocktail bars, coffee shops, and hip restaurants. Still, the original core of the neighborhood is intact, and promises to remain so for many decades to come. After all, it’s one of the city’s most visited, loved, and culturally valuable neighborhoods.